Windbreak

Critical Living Infrastructure

Windbreaks serve several important functions in the Iowa landscape, and can be seen anywhere from farm fields, to home gardens, to city landscapes. Especially after a devastating derecho in 2020, Iowans know the damage of high winds and are finding creative ways to prevent destruction from wind. In rural spaces windbreaks boost crop yields by shielding plants from drying winds, protect livestock from bitter winter wind, reduce soil erosion by wind and water, create wildlife habitat, and help manage snow drifting. In urban spaces windbreaks can muffle noise, block unsightly views, manage wind tunnel effects, and create wildlife corridors.

However, many of Iowa’s windbreaks are in peril. Losses to the 2020 derecho, windbreak age, improper management, and drought/flood cycles are just some of the many factors impacting modern windbreaks. The largest factor for the failure of windbreaks to function properly is the over reliance on a few species of conifers. Even further to the long-term detriment of windbreaks, individual windbreaks are often comprised of only a single species at a time.

To combat this widespread failure of windbreaks, it is now recommended to plant a diversity of tree species and include deciduous trees in combination with conifers.

Why Deciduous Trees?

While many windbreaks are planted with conifers because of the desire for year round protection and functionality, the combination of conifers and deciduous trees can greatly increase the functionality and longevity of a windbreak. Opening the possibilities to deciduous trees also provides a much larger palette and species options for various exposures, soil types, and other environmental factors. While the wind protection benefit between conifers and deciduous trees is not comparable, multiple rows of deciduous trees can provide the same effects as a single row of conifers. Some deciduous species even exhibit a trait called marcescence, holding onto their leaves deep into the winter providing significant wind protection and privacy. Flowering trees used in windbreaks can add an aesthetically pleasing component to windbreaks, or even be used to mask smells from surrounding areas. In terms of wildlife habitat, using a diversity of tree species boosts the ecological benefit of a windbreak and the attractiveness to more species of animals.

Windbreaks for Wildlife

Often wind protection and economic benefit are the primary purpose of windbreak design and function, but windbreaks can also be an incredible habitat for wildlife. Windbreaks can serve wildlife by providing a source of food, shelter for nesting or rearing their young, and protection from predators and the elements. Thoughtful plant selection and design considerations can help create a functional windbreak that takes care of creatures.

One of the most important design considerations for wildlife is planting native mast-producing species. A mast-producing species is one that produces abundant fruit/seeds, often synchronized with other similar species. Maybe the most famous here in Iowa are oaks and hickories, producing a vast number of acorns and nuts every 2-5 years. However there are dozens of mast tree and shrub species native to Iowa.

Another important consideration is if the tree/shrub species is browse for herbivores or a host plant for insects. Choosing native tree species and a mix of conifers and deciduous can provide a substantial food source for native mammals large and small while also serving as hosts for the next generation of insects.

Flowering trees and shrubs can provide an incredible amount of nectar and pollen to native pollinators. Planting a diversity of flowering trees that have different bloom times can even provide nectar for a significant portion of the growing season, strongly boosting the local pollinator population. Many birds are also attracted to flowers as a nectar source.

Finally, providing shelter is a significant consideration for designing a windbreak for wildlife. Conifers are great cover for many creatures, providing a safe place to hide, keep out of bad weather, or to build a nest. Meanwhile many other creatures like to open branching structure of deciduous trees to make a home. Shrubs are also a favorite for many species. Whatever the case, the more plant diversity designed into the windbreak, the more wildlife will take shelter or reproduce in the windbreak.

Overall, an ecologically productive windbreak for wildlife will be designed with a multitude of species that produce fruit/nuts, provide browse or forage for insects and herbivores, nectar and pollen for pollinators, or provide shelter in some way for various animals. The ideal windbreak consists of 5-6 or more rows of woody plants, each row a different height to create lots of diverse habitat. Rather than mowing between trees, establishing prairie, meadow, or savanna understory vegetation will create an incredible designed habitat. The ecological benefit of a windbreak only increases as it ages, providing decades of increasingly valuable habitat.

Windbreak Layout

Protect provided by a windbreak depends heavily on its layout. In general, it is expected that the protection zone of a windbreak relates to the tallest tree height. A windbreak will reliably reduce wind on the leeward side for a distance of 10 to 30 times the tree height, depending on tree species and number of rows. For example, a row of trees 30 feet tall will reduce wind for a distance of 300 feet on the leeward side. Taller trees and an increased number of rows will significantly increase the distance of protection.

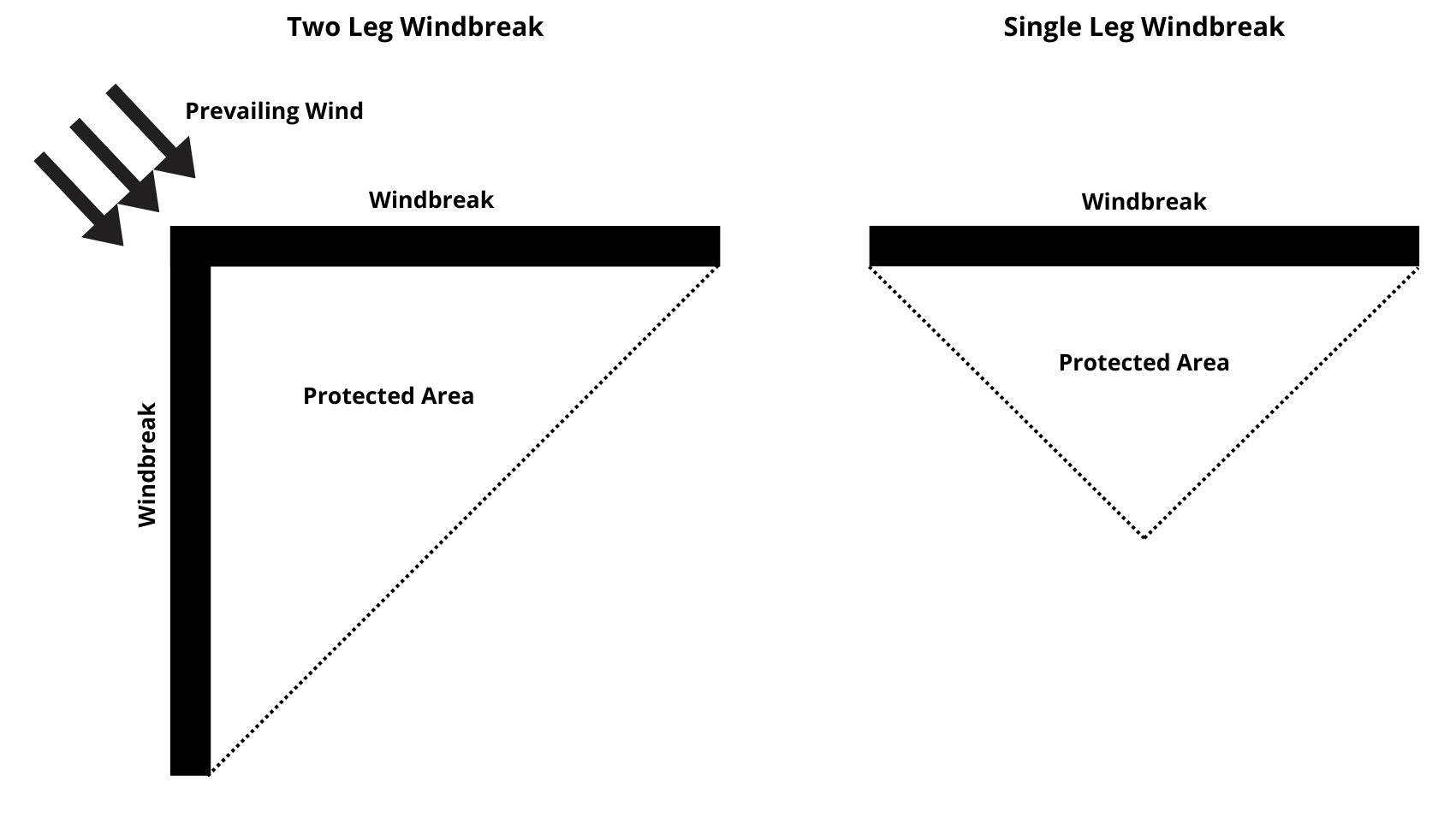

Tree height and number of rows aren’t the only considerations for a protection area. The more directions the wind can be reduced from, the larger the zone of protection. For instance, Iowa receives most of its severe wind from between north and west, so a two leg windbreak perpendicular to those two directions offers a large zone of protection. Meanwhile a single leg windbreak only protects a small triangle from one direction.

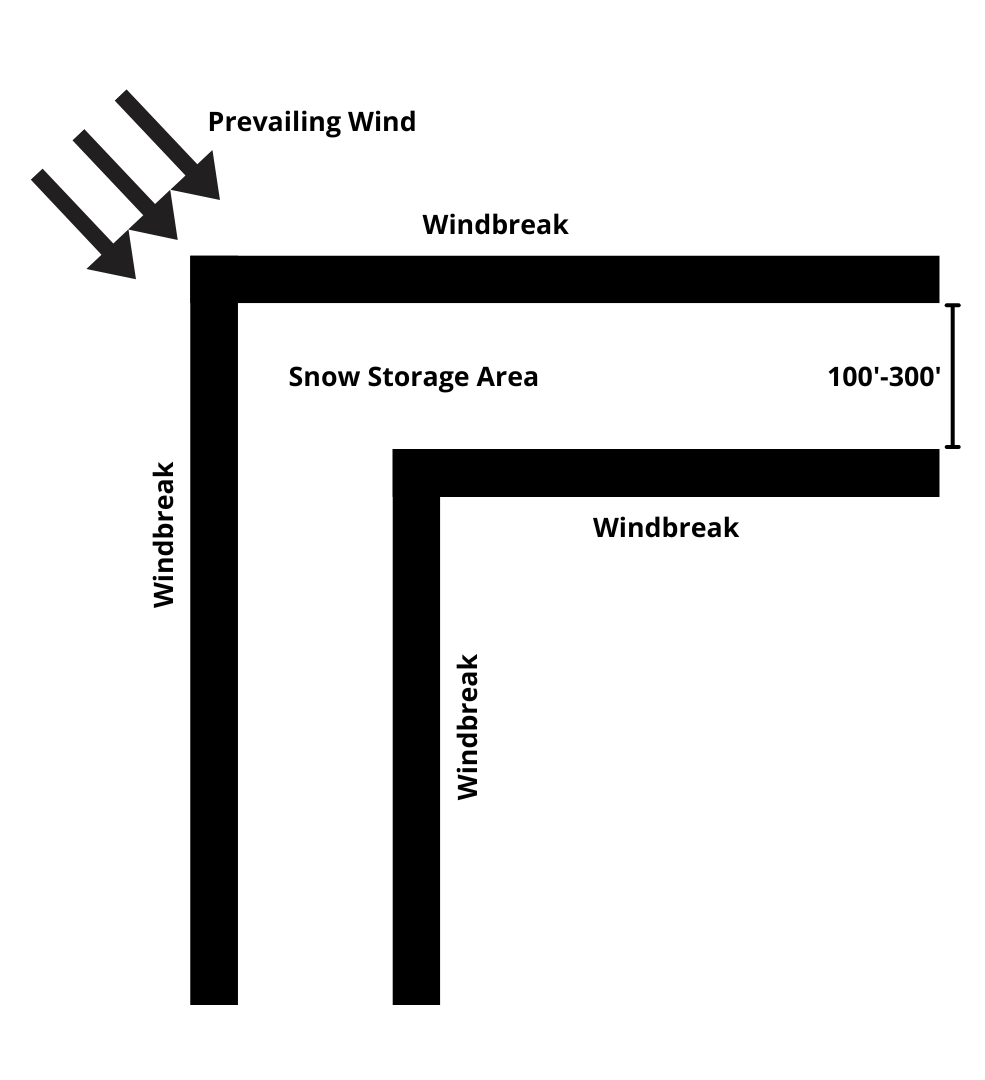

Multiple windbreaks provide the greatest protection downwind and can afford strategies for sheltered access points, areas of extreme protection, or to manage specific windbreak effects. For example, in treeless rural areas or flat farmland it can be difficult to manage snow drifting. Especially around roads, buildings, and vehicles, a small amount of snow can create massive drifts if there is nowhere else for it to accumulate. Layers of windbreaks create pockets of snow storage areas where large drifts can form and accumulate, preventing snow buildup on the leeward side of windbreaks. In areas particularly impacted by drought, these snow storage areas can bank moisture for months into the growing season, providing much needed ground water as weather starts to get dry. Especially in the arid west, double layer windbreaks are one of the few ways to collect seasonal moisture when the only precipitation available for most of the year is snow! For wind sensitive crop species, the space between windbreak layers offers superior year-round protection. For windbreak designers with wildlife habitat goals, multiple windbreaks can provide a scale of magnitude greater habitat than one windbreak alone. One windbreak is great, but more is more!

Iowa Arboretum & Gardens Windbreak

The Iowa Arboretum and Garden’s current windbreak was planted over several years beginning in 2022. The design and plant lists were meticulously drafted by the arboretum’s curator. Several rows of woody plants begin on the windward side with shrubs, small trees, gradually growing to large deciduous trees. These three to four rows of trees reduce the wind speed and directs much of the wind up and over the windbreak, a phenomenon called wind lift. The primary function is to prevent the full brunt of wind hitting the deeper conifer layers and causing breakage, as was seen during the 2020 derecho. The deciduous trees reduce the wind load and diffuse the stress of high winds across a much larger group of trees. The conifers five and six layers deep then further reduce wind speed. Individual rows of trees were planted at their maximum recommended spacing to extend the life of the windbreak beyond the average 50-75 years. It will take several years for the full effects of the windbreak to begin, but the windbreak itself won’t need replacement for hopefully 100 years or more.

The design of the windbreak is meant to achieve several main goals:

The first goal is to weaken wind onto the arboretum’s grounds and protect the collection from damaging high winds. While many of the arboretum’s trees are tolerant to wind, excessive drying winds during the winter and hot dry air during the summer can wick moisture from trees resulting in dieback. The arboretum regularly experiences wind speeds greater than 40 mph, so keeping more delicate trees protected is important. While many people plant windbreaks as a living snow fence, the purpose of the arboretum’s windbreak design is to keep as much snow from blowing off the property as possible. The species selected and tree spacing provides low density, so wind is slowed down rather than blocked. Snow spreads and settles on the leeward side of the windbreak, melting slowly and percolating deep into the ground, making the surrounding landscape more resilient to drought conditions.

The second goal is to serve as an experiment and demonstration of a wide range of native tree species that can be used in windbreaks. Over three dozen tree species have been used in this windbreak so far, including oaks, hickories, maples, hackberries, buckeyes, and much more. This great diversity of trees gives the arboretum the ability to evaluate the performance of specific trees as a windbreak tree recommendation. The diversity of tree types also means that the windbreak as a whole will have a resilient future, diseases and pests will not be able to wipe out large sections of the windbreak at once. Individual trees may need to be replaced over time, but the windbreak as a whole should live for a century or more. Many of the trees were selected based on observations of those species surviving the 2020 derecho across the state. Whether growing in upland woodlands, as sentry trees on hillsides, urban street trees, or even surviving windbreaks, most of these species have been shown to be resilient and resistant to high winds. Most of the trees were also planted as small saplings so the trees could grow up adapted to the wind load.

The final goal is to provide food, shelter, and safe passage for wildlife on the arboretum’s grounds. Every species chosen had to check several boxes involving native ecology while also being able to tolerate strong winds. Oaks, hickories, buckeyes, and other mast species provide vast amounts of food for many animal species during the important season that they are preparing for winter. Maples, lindens, hackberry, serviceberry, and several others provide fruit and seeds much of the rest of the year. Junipers provide berries over the winter that birds especially relish. Serviceberry, linden, maple, redbud, and sumacs provide nectar and pollen to hundreds of native pollinators throughout the summer. Meanwhile all of the woody species selected are the host plants to many insects including caterpillars, beetles, and wasps. The branching structure, fruit, leaves, or twigs of most of the planted species provide shelter and nest material for birds and mammals. As the trees grow their canopy will overlap and get denser providing a shelter for roosting and protection from the elements. Finally, the arboretum is surrounded by natural lands, so this windbreak design creates little avenues for creatures to cross the arboretum’s grounds safely between natural spaces. Animals spotted crossing the grounds in the windbreak includes squirrels, raccoons, opossums, bobcats, turkeys, mink, groundhogs, snakes, bobwhites, pheasants, foxes, coyotes, and many more!

Original Windbreak

The original windbreak was established in 1982 as a collection, but added on as a two-part collection with deciduous and coniferous windbreak designations several years later. Several species of spruce, pine, and arborvitae maintained the density of the Iowa Arboretum north windbreak. Unfortunately, the north side windbreak suffered extensive damage in the August 2020 derecho; the bulk of the trees needed to be removed. The windbreak on the west side, a row of Quercus bicolor, swamp white oak, remained virtually untouched.

The Iowa Arboretum & Gardens thanks the Des Moines Founders Garden Club for helping fund the planting of the new windbreak as well as planting a large portion of the trees as a service project.

Back to Our Plants hompage