PRAIRIE RESTORATION

Experiment in Conservation

Established in 1992, the 4 acre Prairie Restoration is often the first look visitors get of the Arboretum as they pass down Peach Avenue. This prairie was originally created as a display of Iowa native prairie species, representing both grasses and wildflowers. In addition to providing a continuously changing display of color, educational programming focusing on the prairie was developed. Overall, the longstanding goals of the Prairie Restoration are to provide an educational tool for native plant identification, seed collection, growing native species, and to be prairie management demonstration.

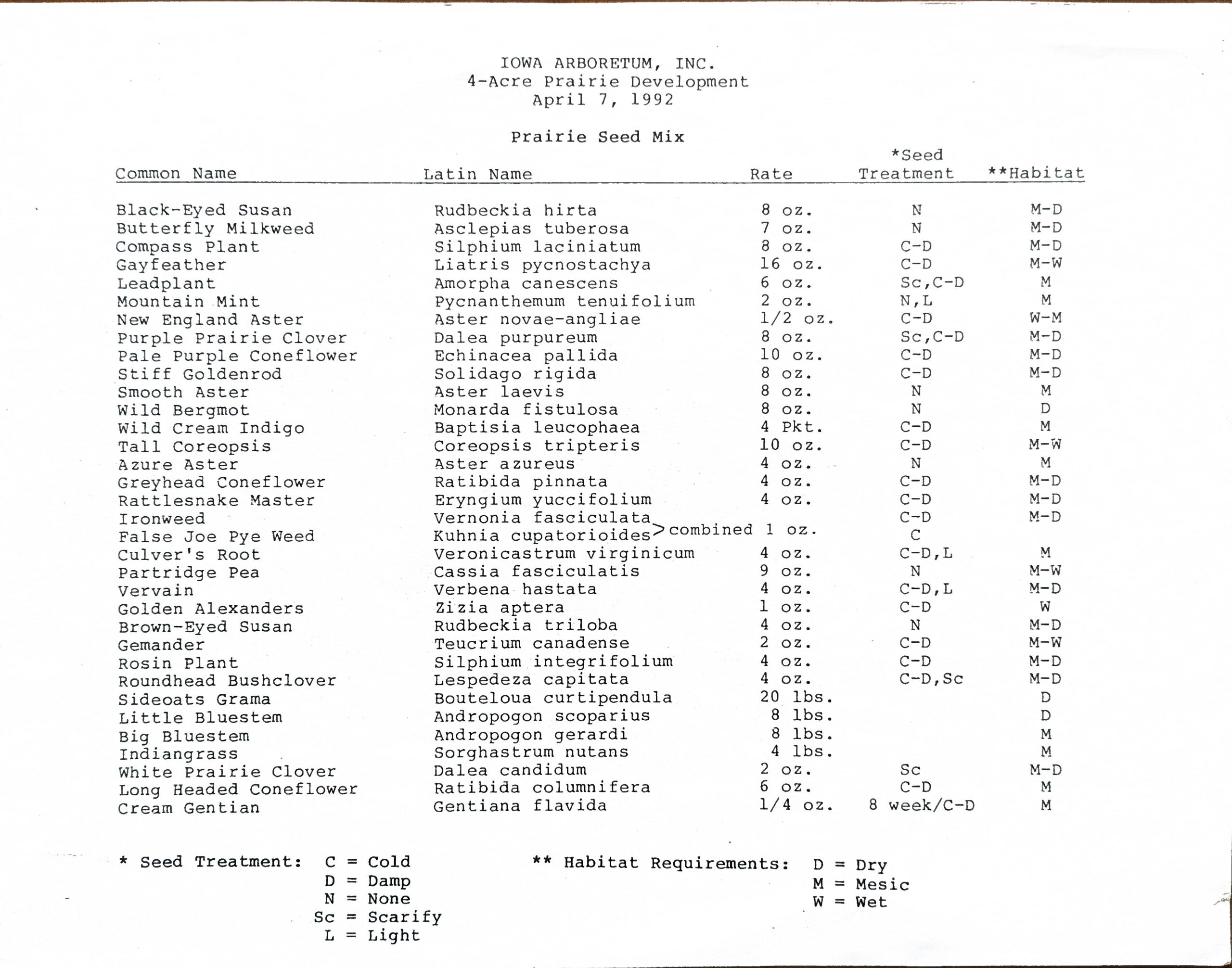

Planning for the installation of the prairie began in the late 1980’s as excitement and popularity of prairie restoration began to spread nationally along with other conservation initiatives. Seed and plant lists were drafted based on plants native to surrounding Boone County, including a recently published flora of Ledges State Park. The architects of the prairie plan wanted to ensure the seeds planted in this particular prairie were also from a local ecotype (a genetically distinct group within a species adapted to its particular habitat, such as altitude, soil type, or water availability, sometimes highly regional). Seed sources were then vetted based on availability of local ecotype seed, or collected from nearby prairies by volunteers.

The bulk of the planning effort was spearheaded by Tre Wilson, the Story County Roadside Biologist at the time. His excitement for a prairie restoration at the Arboretum was future focused, hoping one day this prairie could provide a reservoir of local prairie genetics for other projects. His cheif concern at the beginning was making sure the restored prairie looked and functioned like a natural, central-Iowa prairie and that the finished planting will be as stable as possible taking into account the existing site conditions.

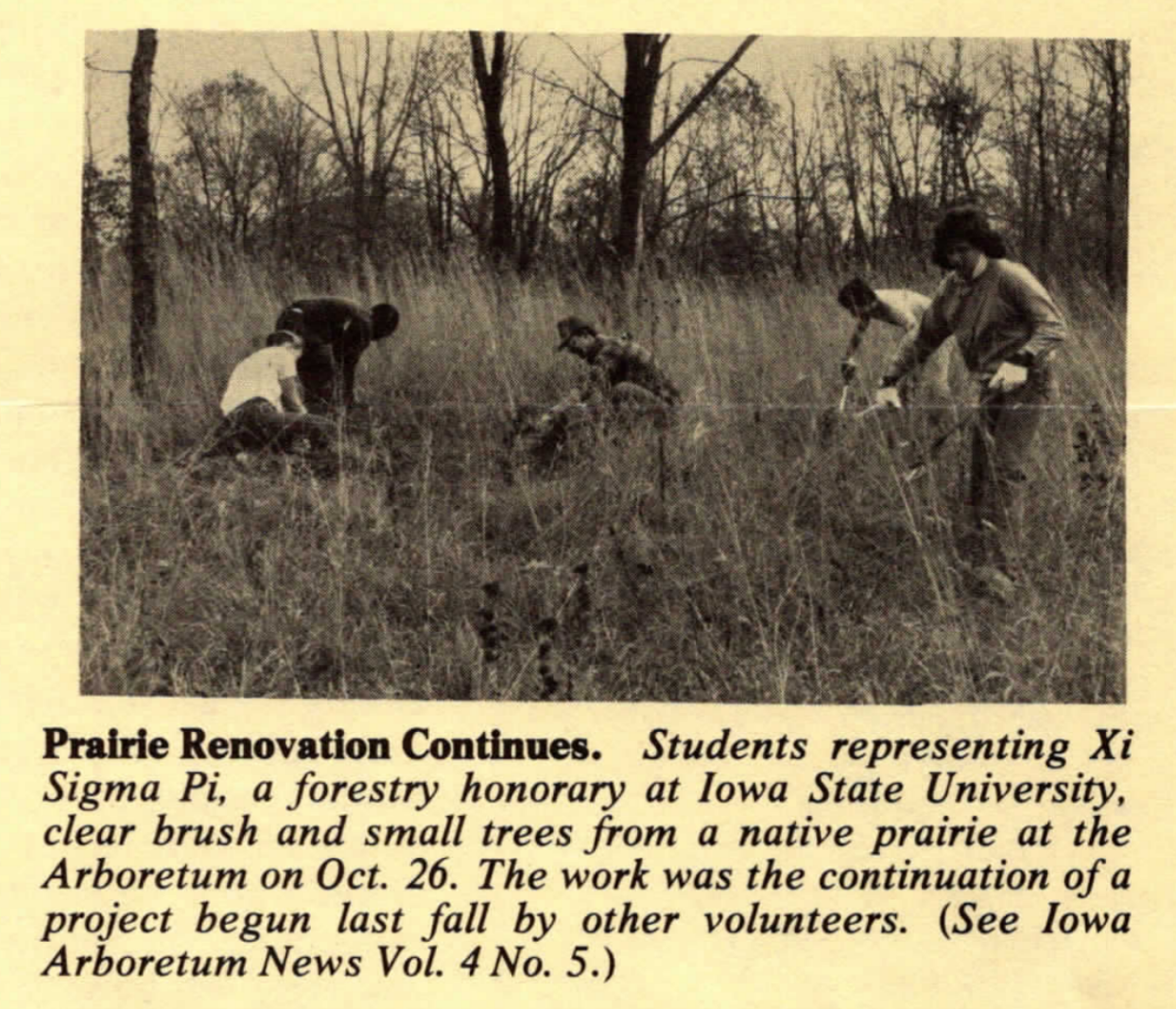

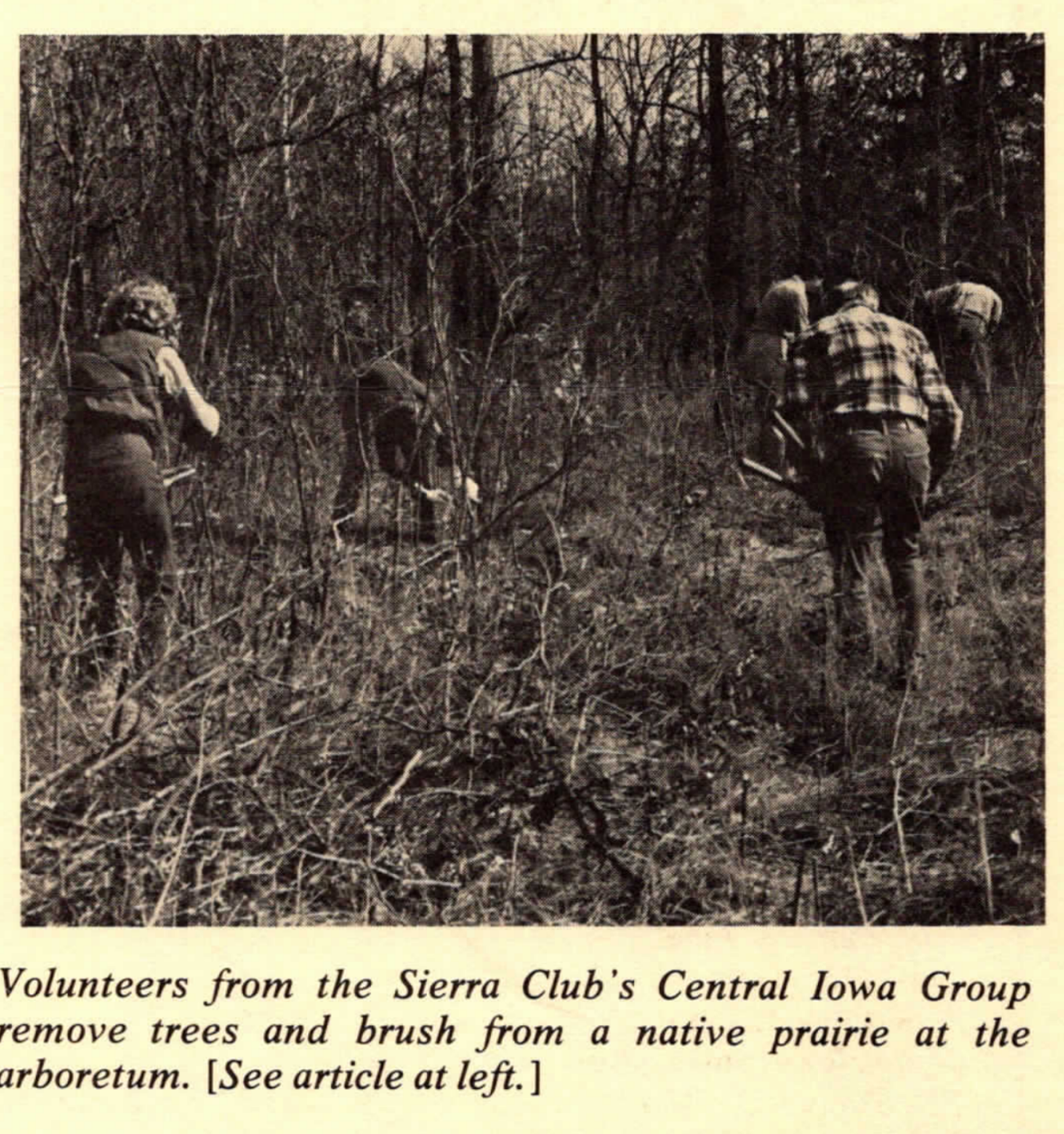

Enthusiasm from Arboretum staff, volunteers, and members led to involvement of several partners to help get the Prairie Restoration planted.

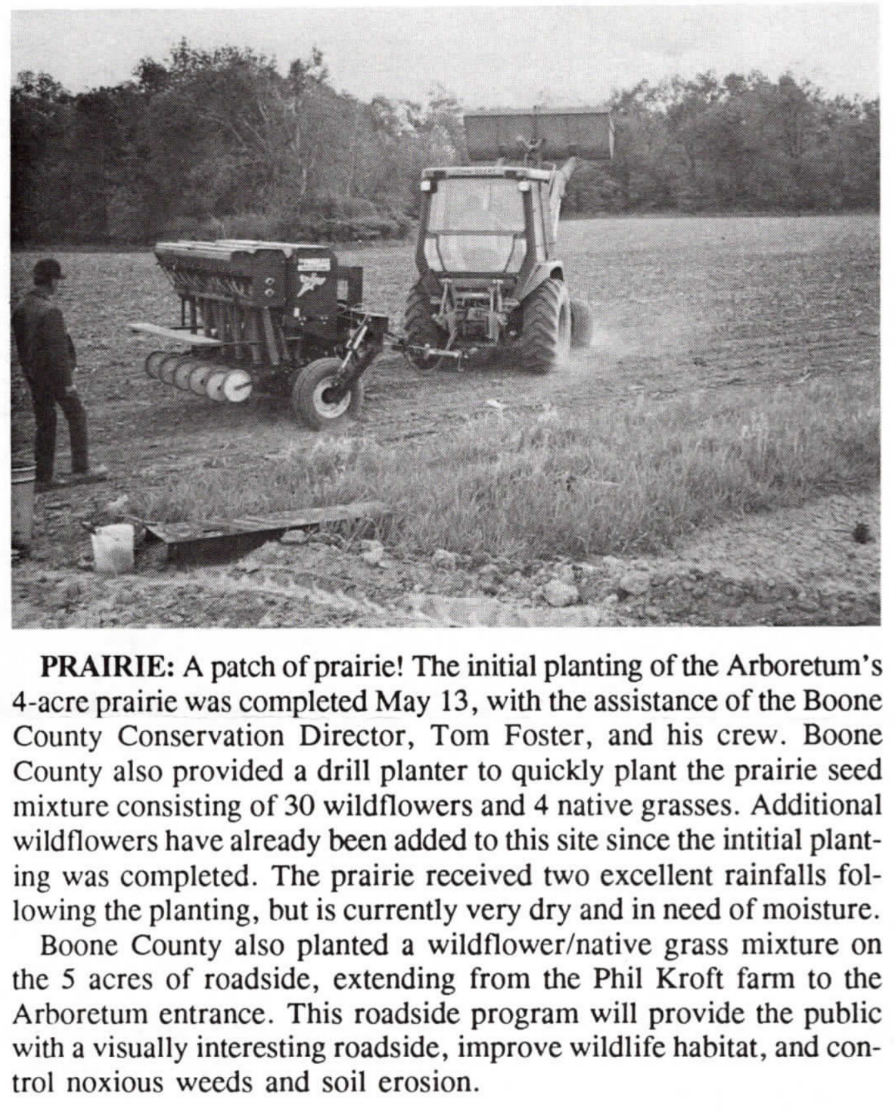

In February 1992, the Arboretum was awarded funding from the Iowa Department of Transportation Living Roadways Trust Fund (LRTF) to complete the 4 acre prairie project. The Boone County Conservation Director at the time then provided the equipment needed and expertise to plant the prairie on May 13, 1992. Using funds awarded to Boone County Conservation by LRTF, 5 acres of roadside on the both sides of Peach Avenue were also seeded to provide a stunning roadway on the way to the Arboretum. Boone County’s goals were to provide wildlife habitat, control noxious roadside weeds, and control soil erosion.

The initial seeding contained 30 species of forbs (wildflowers) and 4 species of native grasses. Much of the seed sourced was from the historic native plant seed supplier Wildflowers from Nature’s Way in Woodburn, Iowa. The owner, Dorothy Baringer, was one of the first people to supply native Iowa seeds in the state and custom collected Boone County seed for this project.

At initial seeding in 1992, a ratio of 50% grass seed to 50% forb seed was applied. Unfortuantely, bizarre weather in the summer and fall of 1992 and then flooding in 1993 caused much of the initial seeding to fail. Additional, LRTF funds were sought to retry the planting in 1994 with the addition of 24 species from seed and 30 species from starter plants. The original goal for the project was to seed 120+ species at initial seeding. Time and funding constraints led to eventual establishment of no more than 45 species of forbs and grasses. Over the years since, additional species have either encroached from surrounding woodlands or were overseeded as part of later LRTF projects.

Land History

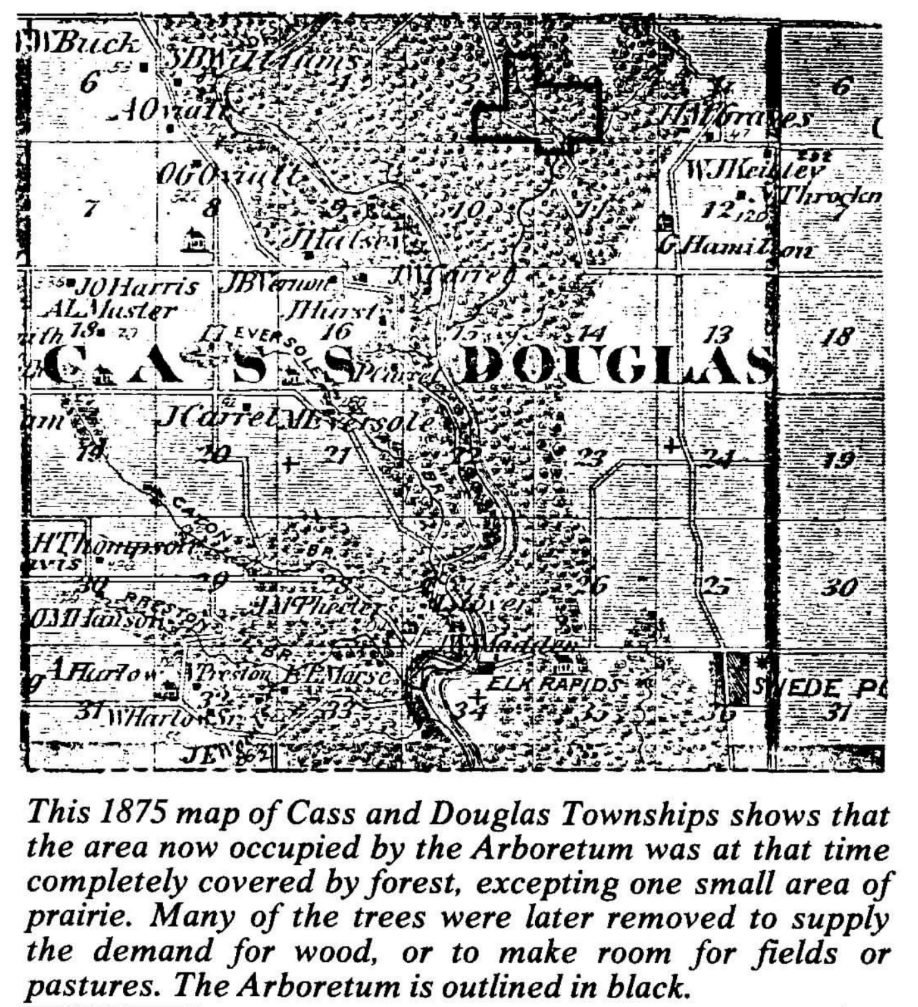

Up until the late 1870’s, most of the Arboretum’s land was upland woodlands. Territory Survey Records from 1847 indicate that the dominating ecosystem for this region was oak-hickory woodland with old growth trees being dated centuries old. An upland surrounded on three sides by water and steep ravines/cliffs, this area was protected from high intensity and frequent burns unlike the prairie uplands nearby. This area would have experienced infrequent low intensity burns generally started by indigenous peoples living in or traveling through the region. However, during settlement of Central Iowa from the 1850’s to 1870’s much of this woodland was logged for timber and to make room for row crop agriculture and fire was suppressed.

The land was farmed and grazed by private land holders until 1950 when it was purchased by the Iowa 4-H Foundation as part of a 1,000 acre land acquisition for the establishment of the Clover Woods Camp & Retreat Center. The Iowa 4-H Foundation continued to farm the land or rent it for farming for several decades. For a total of over 100 years, the land where the Prairie Restoration is today was cultivated.

In 1969, one year after being established, the Arboretum began a 99 year lease of the land from the Iowa 4-H Foundation. Although the 4-acres of land the Prairie Restoration is planted on remained farmland, the Iowa Arboretum took over management of 300 acres of woodlands surrounding the land. In 1991 with excitement building about the prospects of creating a prairie restoration, the Iowa 4-H Foundation Board of Directors agreed to the Arboretum’s proposal to take the 4 tillable acres and convert it to a Prairie Restoration. Although the Arboretum did not yet own the land, it was agreed that the Arboretum would be responsible for establishing and stewarding the prairie. Eventually in 2018 the Arboretum purchased 80 acres from the Iowa 4-H Foundation including this 4 acre prairie restoration.

Extent of Human Activity

Depicted below is a 1930’s era aerial photograph taken by the United States military in conjunction with the United States Geological Survey. In the photograph you can see the original 40 acres of the Iowa Arboretum and Gardens was still woodlands at that time (rare for Central Iowa) meanwhile the surrounding land had been converted from woodland to prairie or farmland. All of the Arboretum’s prairies were cultivated in agriculture for at least 100 years. Sparse canopy in the woodlands also indicated significant timber harvest, likely in the 1910’s-1920’s. Even some of the prairies created from logging back then are back to woodland today.

Prairie Reasearch

After planting in 1992 was finished and several years given for strong establishment, the Arboretum began conducting reasearch on the long-term success of the Prairie Restoration.

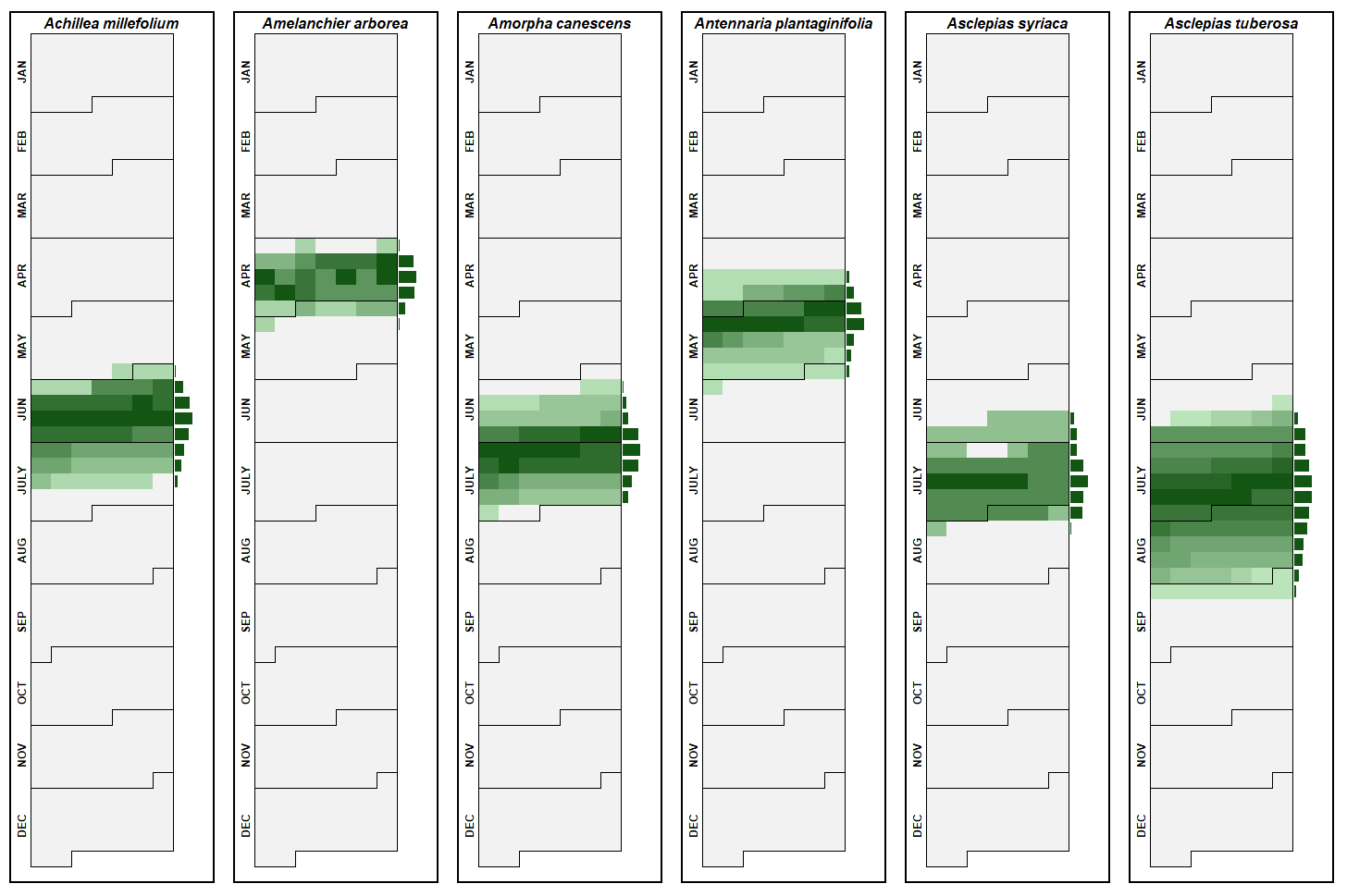

The longest running research project is the collection of phenological data, specifically the bloom period of native plants over time. For decades, staff and volunteers have walked the Arboretum’s natural resources and catalogued plants that were blooming at certain intervals throughout the year. This data is then compiled into models to show the regular bloom period of those plants. Perhaps more applicable after decades of reasearch is the ability to compare contemporary blooming trends with historical bloom periods. Nationally, native plants are blooming earlier, faster, and for shorter periods threatening pollinators and the greater ecosystems they are a part of.

The Arboretum’s own data is indicating that our native plants are blooming up to a week earlier compared to 30 years ago, bloom period is reduced by 20-30%, and plants that maybe had some overlap in bloom time are now all blooming at once. This accelerated and uniform spring green up and summer flowering is one of the causes of decreasing insect diversity globally. To view a compiled version of the phenological models, click here.

Additional research has been conducted to evaluate the long-term success, diversity, and composition of the Prairie Restoration. For instance, in 2010, Drake University student Bailey Johansen under the guidance of Dr. Thomas Rosburg conducted a late-summer prairie assessment. The initial goal of the assessment was to compare existing species composition, abundance, and diversity compared to what had been planted 20 years prior. A second assessment was done in 2024 by Iowa Arboretum and Gardens intern Victoria Pavik as part of her internship while studying ecology at Northwestern College. Her assessment was conducted over the majority of the summer season to compare initial planting, the 2010 assessment, and existing plant diversity.

Both assessments concluded that there had been significant changes in species composition and diversity over time. Overall diversity over the last 30 years has nearly doubled from 34 species to well over 60. However, there was a significant decline in species richness in the 2010 assessment. One catalyst for the change was that the initial seed list failed to account for the amount of moisture in the soil. The Prairie Restoration soil type is most commonly associated with wet upland woodlands, so any species needing dry conditions would have eventually died out. Even whole sections of the prairie have moss serving as the main groundcover. A second conclusion was that laissez-faire prairie management for decades had allowed warm season grasses to dominate, decreasing diversity in the center of the prairie. Resumed regular management in the late 2010’s to early 2020’s greately decreased warm season grass pressure and increased diversity.

Third, species encroachment from the surrounding woodland or seed spread by animals contributed to additional diversity. In particular, new species were often found along woodland edges or deer paths, indicating animal help and residual woodland populations. Finally, additional species may have been added over time from reseeding efforts in the ditch nearby, roadside overseeding, or seeds hitchiking on equipment used in management.

These assessments are a helpful tool to track progress as the prairie matures and stabilizes. The greater the diversity, generally the more stable. Likewise, a greater number of plants species reasonably accomodates a greater number of animal, fungal, and microbiotic species.

Curiously, several species considered to be rare in this part of Iowa have been surveyed in the Prairie Restoration. This includes slender false foxglove (Agalinis tenuifolia), prairie shooting star (Dodecatheon meadia), hybrid bottle gentian (Gentiana x pallidocyanea), Michigan lily (Lilium michiganense), winged loosestrife (Lythrum alatum), and horse gentian (Triosteum perfoliatum).

Prescribed Fire

Prairies are complicated systems with diversity beyond comprehension. Interactions of insects, mammals, birds, fungi, microbiota, and plants depend on seasonal fire to maintain their processes. Fire is a necessary process that shapes and manages these ecosystems and complicated relationships, and even untouched/remnant ecosystems are being degraded due to the loss of fire.

What exactly does fire do? Research is only just now catching up with how our ecosystems interact with fire.

The largest ecosystem function of fire in prairies is that it directly manages woody plant encroachment into tallgrass prairie. This is important to maintaining the ecosystem structure many organisms depend on, especially insects, birds, and mammals. In prairies, fire manages willows (Salix sp.), sycamores (Platanus occidentalis), dogwoods (Cornus sp.), viburnums (Viburnum sp.), sumac (Rhus glabra), ash (Fraxinus sp.), cedars (Juniperus virginiana), brambles (Rubus sp.), gooseberry (Ribes missouriense), poison ivy (Toxicodendron pubescens) and many others. Lack of burning or long-term laissez-faire management can transition prairies into shrublands, becoming difficult to return to prairie without extraordinary measures and quickly decreasing plant diversity.

Fire is also incredibly important in the nutrient cycle of North American ecosystems. Warm season grasses heavily feed on nitrogen, depleting it from the surrounding soil and making it unavailable for forbs in the same system. Fire returns nitrogen back to the surface of the soil in the form of ash while also slowing grassy and woody species down for the following season, allowing forbs an important competitive advantage, open sunlight, and promoting ecosystem diversity. Time of year considerations can swing plant competition in specific directions too. For instance burning in late fall returns nitrogen to the soil before spring and reduces above ground biomass. Sunlight then warms the soil faster than unburned prairies, quickly flushing forbs and wildflowers long before warm season grasses. Repeat fall burns can swing competition and composition in favor of a more florally abundant and diverse prairie over time.

Third, many prairie plant species require fire stratification or smoke treatment for seed germination. As mentioned earlier these systems are incredibly complicated and diverse. Many plants have evolved to take advantage of the bare ground available immediately after a fire for less competition during seedling establishment. These seeds take chemical cues from smoke to signal readiness to germinate or some have physically tough seed coats that can be broken by fire to break dormancy. Fire and smoke dependent plants are disappearing at an alarming rate due to 150 years of historical fire suppression, and it has been proposed that we don’t even know the scale at which diversity has already been lost.

Lastly, fire is one tool in management of non-native species in prairie systems. Since the colonial settlement of its land, Iowa’s ecosystems have been under siege by a scourge of non-native aggressive plants. Species of special concern cataloged in great numbers in Central Iowa prairies include honeysuckles (Lonicera maackii, L. x bella, L. morrowii, and L. tatarica), Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii), multiflora rose (Rosa multiflora), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), olives (Elaeagnos angustifolia and E. umbellata), Amur cork tree (Phellodendron amurense), Amur maple (Acer ginnala), burning bush (Euonymus alatus), white mulberry (Morus alba), Korean boxwood (Buxus macrophylla var. koreana), yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus), reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea), bird’s-foot trefoil (Lotus corniculatus), and Chinese silvergrass (Miscanthus sinensis). Amur cork tree, Amur maple, burning bush, Chinese silver grass, Japanese barberry, Korean boxwood, yellow flag iris, and likely others were once intentionally planted for ornamental value at the Arboretum and have since escaped into the surrounding ecosystems. Fire is a tool to not only keep these plants from growing to their full size, but can disrupt reproduction by killing seeds and seedlings not fire resistant. Many of these plants after repeated fire exposure, chemical tools, and manual removal also cannot survive in the long-term.

Back to Our Plants hompage

Back to Natural Resources hompage